Inside the architecture: How software-defined vehicle (SDV) platforms are built

December 16, 2025 10 min read

The dashboard touchscreen flickers to life. Within seconds, new driving modes and features appear, the ones that weren’t there yesterday. No mechanic opened the hood. No technician plugged in a diagnostic tool. The car learned something new overnight, downloading capabilities the way your phone pulls in the latest app update.

Welcome to the era of software-defined vehicles (SDVs), which signals — now, the line between automobiles and computers has blurred completely. In this article, we’ll examine the basis of architectures that empower these software platforms on wheels.

The old architecture is broken

Traditional cars weren’t built this way. For decades, automakers assembled vehicles from discrete systems (like braking, steering, and climate control). Each was governed by its own computer or electronic control unit. A modern luxury vehicle might contain anywhere from 100 to 150 of these units, each running proprietary code, connected through a labyrinth of wiring that could stretch for miles if laid end to end.

Another crucial detail is that these distributed systems couldn’t communicate in the past. Your windshield wipers functioned properly, but they had no way to check if you had enough washer fluid to reach your destination. Problems like this become critical when vehicles need to make autonomous vehicle systems.

The solution automotive engineers have converged on sounds almost too simple: consolidate computing power. Rather than scattering intelligence across dozens of small computers, it was possible to concentrate it in a few powerful nodes. But getting there requires understanding two different approaches to organizing vehicle electronics, and why the industry is betting its future on one over the other.

Domain-based architecture

Before vehicles can make the leap to fully software-defined platforms, most should pass through what the industry calls domain-based architecture. This approach embodies an evolution from the distributed ECUs, but it’s increasingly clear that it’s not the final destination.

In domain architectures, OEMs organize vehicle functions by type rather than location. A domain controller manages all aspects of a functional area. Here, everything related to powertrain sits under one controller, while safety systems like braking and stability control fall under another. Common domains include the engine, braking system, and steering system, with each domain having its own dedicated controller managing these operations.

The domain approach brought immediate benefits. Instead of dozens of ECUs communicating through multiple networks, a handful of domain controllers could coordinate complex operations. Vehicle software development became more manageable when engineers could focus on discrete functional areas. Updates and validation followed clearer paths through the organizational hierarchy.

But domain-based architecture carries an inherent limitation. Many domains physically span the entire vehicle, which means wiring still snakes from front to rear, and it adds weight and complexity. The engine domain needs sensors in the rear, the safety domain requires components throughout the chassis, and infotainment touches every corner of the cabin.

OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers are making the transition from domain-based architecture to zonal architecture. Financial pressure is mounting. They recognize that incremental improvements won’t close the competitive gap with software-first manufacturers.

Zonal architecture for SDVs

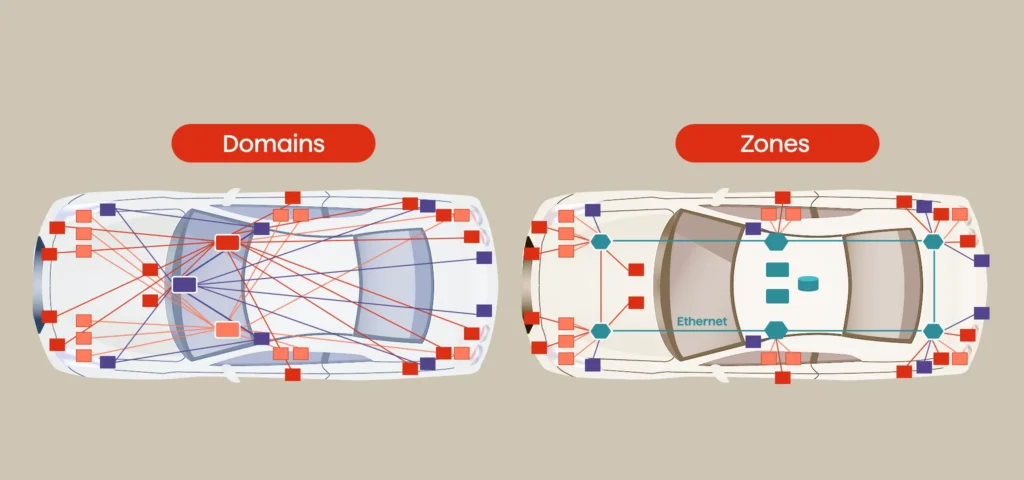

Zonal vehicle architecture alters the script. It groups electronics by what they do instead of where they are located (see Graph 1).

The vehicle is divided into regions, e.g., front-left, front-right, rear-left, and rear-right. Each zone receives its own controller that manages every sensor, actuator, and component within its physical area, regardless of function. The front-left zonal controller might handle headlights, turn signals, radar sensors, door locks, and window motors simultaneously. Devices of various functions attach to the closest gateway, rather than with its domain grouping.

These zonal controllers then connect to a central computing unit via high-speed Ethernet. This approach creates what amounts to a nervous system organized around proximity rather than purpose. The architecture mirrors how data centers are built, with edge nodes feeding information to central processors through high-bandwidth connections.

The benefits are strikingly evident in the supply chain. Zonal wiring architectures reduce cable length and save substantial amounts of copper per vehicle. When you’re manufacturing millions of vehicles annually, those savings become substantial.

Zonal architecture also enables scalability that domain-based systems can’t match. Automakers can easily scale zonal architecture up and down to support more sensors and electronics throughout the vehicle. Adding a new feature doesn’t require redesigning the entire network. It just means updating software on the relevant zonal controller.

The architecture also tackles a critical challenge for over-the-air updates. The OTA system in zonal architecture is simpler in general as the whole idea is based on abstracting software from hardware, and less tightly coupled software is way easier to update remotely. This independence matters tremendously as vehicles accumulate millions of lines of code that need continuous maintenance.

Not everyone moves at the same pace. By 2030, the global share of vehicles with zonal architecture is expected to reach around 18%, while domain-based architectures will account for 48% and distributed architecture for 34%. Legacy architectures will persist as older platforms continue production, and manufacturers adopt hybrid approaches during the transition.

The technical backbone of a software-defined vehicle

Making zonal architecture work requires infrastructure that didn’t exist in traditional vehicles. Legacy networks like CAN-FD can’t handle data volumes. High-resolution cameras, lidar arrays, and centralized computing all demand bandwidth that older protocols simply cannot provide.

The industry’s response has been a wholesale migration to automotive Ethernet. In-vehicle networking takes its roots in IEEE 802.1AS-2020, the IEEE-approved standard for timing and synchronization in time-sensitive networking applications. This deterministic Ethernet ensures that critical safety data arrives exactly when needed, and lower-priority information flows through the same network without delays.

Within each zone, things get more complex. A significant amount of CAN infrastructure will exist in both CAN FD and CAN XL formats, connecting the zonal controller to various edge ECUs and sensors. Vehicles should support various protocols: Bluetooth and USB for mobile devices, MIPI for cameras, and different internally developed standards. This heterogeneity reflects automotive development that will persist for years as new and old systems coexist.

Layers upon layers

SDV platforms are typically built in distinct architectural layers, much like modern smartphone operating systems. At the foundation sits the hardware abstraction layer, which provides a consistent interface between the physical components and the software running above. This allows engineers to update or swap hardware without rewriting every application.

Above this runs the middleware, the connective tissue that handles critical functions like communication between different software modules, security protocols, and resource management. This layer is crucial but invisible to drivers. It guarantees that when you press the brake pedal, that signal reaches the appropriate systems within milliseconds.

The application layer is where drivers interact with the vehicle. This includes everything from the user interface on the central touchscreen to the algorithms controlling adaptive cruise control. Because these applications run on a standardized platform, they can be updated over the air, just like apps on a smartphone.

The economic advantage

The financial dynamics driving this transition extend beyond manufacturing savings. The software-defined vehicle market is projected to grow from $213.5 billion in 2024 to $1.23 trillion by 2030, driven largely by the ability to monetize features after purchase.

This creates new business models. BMW offers driving assistants and traffic camera information as subscription services. Mercedes-Benz lets customers activate advanced driver assistance features on demand. The economic potential of these recurring revenue streams has captured executive attention across the industry.

The market for over-the-air updates (the mechanism enabling all this) stands at $4.78 billion in 2025 and is forecast to reach $11.23 billion by 2030. That growth embodies a shift in how automakers generate revenue and maintain customer relationships throughout vehicle ownership.

Regional dynamics and competition

Western automakers aren’t the only ones racing toward software-defined architectures. Chinese manufacturers like BYD, NIO, and Li Auto deploy state-of-the art architectures and often move faster than their European and American counterparts.

In fact, U.S., European, and Japanese OEMs have been facing multiple challenges in SDV development. They have been struggling for the past half-decade to figure out which is the best approach to developing EVs, undergoing multiple shifts in both hardware and software architectures.

In an IBM survey of 1,230 automotive executives, the technical challenge of separating software and hardware layers was identified as the top challenge, with 77% facing a lack of software development tools and methodologies. Of equal concern, 74% of respondents reported that a strong mechanical-driven culture is making it difficult to switch to software-driven product development.

Such competition makes clear that success in software-defined vehicles requires more than incremental improvements to existing processes. It demands fundamental organizational transformation, massive R&D investment, and the ability to move at software industry speed.

The security question

Concentrating so much functionality in centralized computers creates an obvious vulnerability. In July 2024, UNECE regulations began requiring every newly approved vehicle in regulated markets to feature a certified software update management system. Manufacturers must document secure pipelines, audit risk mitigation, and maintain incident response mechanisms for the full product lifecycle.

The regulatory pressure is accelerating investment in cryptographic signing, secure boot capabilities, and rollback mechanisms that let vehicles recover from failed updates. The global patchwork of regulations adds complexity, but it also establishes baseline security expectations that the industry had previously lacked.

Final thoughts

As software-defined vehicle platforms mature, they’re enabling capabilities that weren’t possible in the past. Vehicles can now improve the driving experience through software updates that add new features or optimize performance. Automakers can collect data to understand how cars are actually used and refine their designs accordingly. New business models emerge around subscription features and services.

The ultimate destination is a vehicle that becomes more capable and valuable over time, a software platform on wheels that evolves with its owner’s needs. Whether automakers can successfully execute this transformation remains the defining question for the industry’s next chapter.

Stay in the fast lane with cutting-edge technologies: talk to Avenga.